สำนักข่าวต่างประเทศรายงานเมื่อวันที่ 4 พ.ค.ว่า นายคริส เจมส์ ชายอังกฤษผู้ตาบอดเป็นเวลา 20 ปี สามารถกลับมามองเห็นอีกครั้ง หลังจากได้รับการปลูกฝังไมโครชิพในดวงตา โดยเขาบอกว่า หลังจากอยู่ในความมืดมานับสิบปี จู่ ๆ เขาก็เห็นแสงสว่างอย่างกระจ่างตา เหมือนมีหลอดไฟอยู่ในดวงตา ขณะที่ความสำเร็จคาดว่าจะจุดประกายตาให้แก่ผู้ป่วยตาบอดในอังกฤษ 20,000 หมื่นคน ที่ตาบอดจากอาการต่างๆ รวมทั้งอาการเสื่อมสภาพของเยื่อชั้นในของดวงตา โดยผู้ป่วยอีกรายที่ตาบอดกลับมามองเห็นก็คือ นายโรบิน มิลเลอร์ โปรดิวเซอร์ดนตรีชื่อดังของอังกฤษด้วย

สำนักข่าวต่างประเทศรายงานเมื่อวันที่ 4 พ.ค.ว่า นายคริส เจมส์ ชายอังกฤษผู้ตาบอดเป็นเวลา 20 ปี สามารถกลับมามองเห็นอีกครั้ง หลังจากได้รับการปลูกฝังไมโครชิพในดวงตา โดยเขาบอกว่า หลังจากอยู่ในความมืดมานับสิบปี จู่ ๆ เขาก็เห็นแสงสว่างอย่างกระจ่างตา เหมือนมีหลอดไฟอยู่ในดวงตา ขณะที่ความสำเร็จคาดว่าจะจุดประกายตาให้แก่ผู้ป่วยตาบอดในอังกฤษ 20,000 หมื่นคน ที่ตาบอดจากอาการต่างๆ รวมทั้งอาการเสื่อมสภาพของเยื่อชั้นในของดวงตา โดยผู้ป่วยอีกรายที่ตาบอดกลับมามองเห็นก็คือ นายโรบิน มิลเลอร์ โปรดิวเซอร์ดนตรีชื่อดังของอังกฤษด้วย

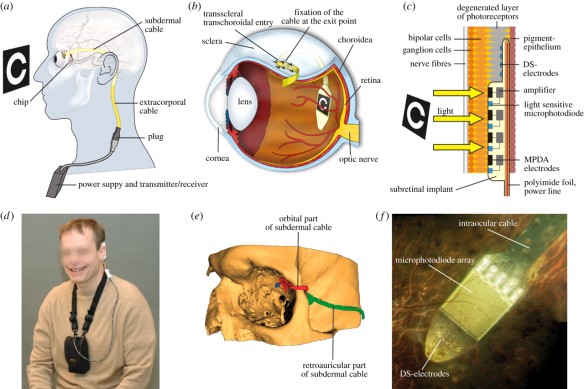

รายงานระบุว่า ความสำเร็จดังกล่าวจากทีมแพทย์อังกฤษซึ่งใช้เวลาผ่าตัดปลูกฝังไมโครชิพในดวงตา ใช้เวลา 10 ชม.โดยไมโครชิพดังกล่าวมีความคมชัดต่อแสงราว 1,500 พิกเซล ซึ่งจะทำหน้าที่แทนตัวรับแสงของดวงตาและกรวยตา และทำงานด้วยพลังงานไฟ้าไร้สายที่อยู่ด้านหลังหู เชื่อมต่อเข้ากับแบ๊ตเตอรี่ที่จ่ายไฟจากจานแม่เหล็กบนหนังศีรษะ อย่างไรก็ตาม นายทิม แจ๊คแมน ศัลยแพทย์ด้านกระจกตาแห่งมหาวิทยาลัยคิง คอลเลจ บอกว่า งานชิ้นนี้ถือว่าเกินกว่าที่เขาและผู้ช่วยคาดไว้ เพราะสามารถทำให้ผู้ป่วยตาบอดสามารถคืนความสามารถในการมองเห็นที่เป็นประโยชน์ต่อผู้ป่วยได้

อย่างไรก็ตาม ศัลย์แพทย์ผู้นี้ชี้ว่า งานชิ้นนี้ยังเป็นขั้นเริ่มต้นเท่านั้น และจะต้องพัฒนาต่อไปเพื่อความสมบูรณ์แบบอย่างถาวร ทั้งนี้ กระบวนการฝังไมโครชิพในดวงตาเพื่อให้ผู้ป่วยมองเห็นยังมีการทดลองในประเทศอื่นด้วย เช่น จีน และเยอรมัน โดยอุปกรณ์ชิพฝังผลิตโดยบริษัท AG ของเยอรมัน

ที่มา: มติชน 5 พฤษภาคม 2555

.

Related Link:

.

First successful retinal implants for the blind from retinitis pigmentosa

Posted on May 7, 2012 by eyedrd

It’s no miracle cure, but new research into retinal implants is showing promising results. Patients in the UK and Hong Kong have been restored rudimentary sight after years of blindness through the use of light-sensitive microchips in the eye.

The idea of a retinal implant is not new, and studies reach back 10 to 15 years, but the science is getting to the point where such a device may actually become a prescribed treatment. The current tests, by German medical research company Retina Implant AG, show that not only is the procedure safe, but even in an early state it can have highly beneficial results for the visually impaired.

Chris James and Robin Millar in the UK and Tsang Wu Suet Yun in Hong Kong are all receiving experimental implant treatment for retinitis pigmentosa. The condition causes the light-sensing retina at the back of the eye to deteriorate, leading to blindness but leaving the optic nerve and vision-processing portions of the brain intact. Of the various forms of blindness, retinal degeneration is the most promising for treatment, as replacing or repairing other parts of the visual system can be far more complicated.

Retinal implants perform the duties of the rod and cone cells in the retina, detecting light and reporting it to the other cells, which then carry that information to the brain. The tiny (0.1 x 0.1 in.) implant being tested on these patients is controlled and powered by a second chip implanted behind the ear — a more accessible location for plugs and buttons than inside the eye.

Retina Implant AG

Model of the retina implant’s output

The image produced by the sensor is low-resolution even under ideal conditions and with the brain interpreting the data correctly, but the patients reported various positive effects. They were all able to orient themselves towards light sources, determine basic shapes up close, and one man even claims it has restored his ability to dream in color.

What was done?

The retinal implants were developed by Retina Implant AG in Germany to treat people with retinitis pigmentosa. Each implant contains a microchip containing 1,500 tiny electronic light detectors. During the trial, the implant was placed beneath the retina at the back of the patient’s eye. The patient’s optic nerve (the nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain) was then able to pick up electronic signals coming from the microchip.

This delicate operation is conducted in two parts:

First, the power supply has to be implanted. This is buried under the skin behind the ear.

Then, the electronic retina has to be inserted into the back of the eye and stitched into position before being connected to the power supply.

Professor Robert MacLaren, who is leading the research, said: “What makes this unique is that all functions of the retina are integrated into the chip. It has 1,500 light-sensing diodes and small electrodes that stimulate the overlying nerves to create a pixellated image. Apart from a hearing aid-like device behind the ear, you would not know a patient had one implanted.”

What is retinitis pigmentosa?

Retinitis pigmentosa is a rare hereditary condition affecting around one in every 3,000-4,000 people in Europe. It causes gradual and progressive loss of the light-detecting cells in the retina. People with the condition often start noticing problems with their peripheral vision and problems seeing in low-light conditions during adolescence. By middle age, many people with retinitis pigmentosa will have greater problems with their vision and some will become blind. There is currently no cure for the condition, so any developments in treatments are a step forward.

How effective was the implant?

Before his operation on 22 March 2012, Chris James had been completely blind in his left eye for more than 10 years and could only distinguish lights in his right eye. When his electronic retina was switched on for the first time, three weeks after the operation, James was able to distinguish light against a black background in both eyes. He is now reported to be able to recognise a plate on a table and other basic shapes, and his vision continues to improve. He said: “It’s obviously early days but it’s encouraging that I am already able to detect light where previously this would have not been possible for me. I’m still getting used to the feedback the chip provides and it will take some time to make sense of this. Most of all, I’m really excited to be part of this research.”

Robin Millar also said he could detect light immediately after the electronic retina was switched on, and that useful vision was beginning to be restored.

How will the results be used?

Ten further patients with retinitis pigmentosa will now receive the implant at the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust and King’s College Hospital in London. Longer-term follow-up of these patients, and the two men who have already been treated, is awaited. Both men are having monthly follow-ups.

Professor MacLaren said: “We are all delighted with these initial results. The vision is different from normal and it requires a different type of brain processing. We hope, however, that the electronic chips will provide independence for many people who are blind from retinitis pigmentosa.”

These clinical trials are expected to last a year if there are no problems, and even if all goes well there are many more obstacles to overcome. But the rapidly advancing research going on worldwide indicates that it is only a matter of time.

Data from: eyedrd.org